The Rust Programming Language

by Steve Klabnik, Carol Nichols, and Chris Krycho, with contributions from the Rust Community

This version of the text assumes you’re using Rust 1.90.0 (released 2025-09-18)

or later with edition = "2024" in the Cargo.toml file of all projects to

configure them to use Rust 2024 Edition idioms. See the “Installation” section

of Chapter 1 for instructions on installing or

updating Rust, and see Appendix E for information

on editions.

The HTML format is available online at

https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/

and offline with installations of Rust made with rustup; run rustup doc --book to open.

Several community translations are also available.

This text is available in paperback and ebook format from No Starch Press.

🚨 Want a more interactive learning experience? Try out a different version of the Rust Book, featuring: quizzes, highlighting, visualizations, and more: https://rust-book.cs.brown.edu

Foreword

The Rust programming language has come a long way in a few short years, from its creation and incubation by a small and nascent community of enthusiasts, to becoming one of the most loved and in-demand programming languages in the world. Looking back, it was inevitable that the power and promise of Rust would turn heads and gain a foothold in systems programming. What was not inevitable was the global growth in interest and innovation that permeated through open source communities and catalyzed wide-scale adoption across industries.

At this point in time, it is easy to point to the wonderful features that Rust has to offer to explain this explosion in interest and adoption. Who doesn’t want memory safety, and fast performance, and a friendly compiler, and great tooling, among a host of other wonderful features? The Rust language you see today combines years of research in systems programming with the practical wisdom of a vibrant and passionate community. This language was designed with purpose and crafted with care, offering developers a tool that makes it easier to write safe, fast, and reliable code.

But what makes Rust truly special is its roots in empowering you, the user, to achieve your goals. This is a language that wants you to succeed, and the principle of empowerment runs through the core of the community that builds, maintains, and advocates for this language. Since the previous edition of this definitive text, Rust has further developed into a truly global and trusted language. The Rust Project is now robustly supported by the Rust Foundation, which also invests in key initiatives to ensure that Rust is secure, stable, and sustainable.

This edition of The Rust Programming Language is a comprehensive update, reflecting the language’s evolution over the years and providing valuable new information. But it is not just a guide to syntax and libraries—it’s an invitation to join a community that values quality, performance, and thoughtful design. Whether you’re a seasoned developer looking to explore Rust for the first time or an experienced Rustacean looking to refine your skills, this edition offers something for everyone.

The Rust journey has been one of collaboration, learning, and iteration. The growth of the language and its ecosystem is a direct reflection of the vibrant, diverse community behind it. The contributions of thousands of developers, from core language designers to casual contributors, are what make Rust such a unique and powerful tool. By picking up this book, you’re not just learning a new programming language—you’re joining a movement to make software better, safer, and more enjoyable to work with.

Welcome to the Rust community!

- Bec Rumbul, Executive Director of the Rust Foundation

Introduction

Note: This edition of the book is the same as The Rust Programming Language available in print and ebook format from No Starch Press.

Welcome to The Rust Programming Language, an introductory book about Rust. The Rust programming language helps you write faster, more reliable software. High-level ergonomics and low-level control are often at odds in programming language design; Rust challenges that conflict. Through balancing powerful technical capacity and a great developer experience, Rust gives you the option to control low-level details (such as memory usage) without all the hassle traditionally associated with such control.

Who Rust Is For

Rust is ideal for many people for a variety of reasons. Let’s look at a few of the most important groups.

Teams of Developers

Rust is proving to be a productive tool for collaborating among large teams of developers with varying levels of systems programming knowledge. Low-level code is prone to various subtle bugs, which in most other languages can only be caught through extensive testing and careful code review by experienced developers. In Rust, the compiler plays a gatekeeper role by refusing to compile code with these elusive bugs, including concurrency bugs. By working alongside the compiler, the team can spend its time focusing on the program’s logic rather than chasing down bugs.

Rust also brings contemporary developer tools to the systems programming world:

- Cargo, the included dependency manager and build tool, makes adding, compiling, and managing dependencies painless and consistent across the Rust ecosystem.

- The

rustfmtformatting tool ensures a consistent coding style across developers. - The Rust Language Server powers integrated development environment (IDE) integration for code completion and inline error messages.

By using these and other tools in the Rust ecosystem, developers can be productive while writing systems-level code.

Students

Rust is for students and those who are interested in learning about systems concepts. Using Rust, many people have learned about topics like operating systems development. The community is very welcoming and happy to answer students’ questions. Through efforts such as this book, the Rust teams want to make systems concepts more accessible to more people, especially those new to programming.

Companies

Hundreds of companies, large and small, use Rust in production for a variety of tasks, including command line tools, web services, DevOps tooling, embedded devices, audio and video analysis and transcoding, cryptocurrencies, bioinformatics, search engines, Internet of Things applications, machine learning, and even major parts of the Firefox web browser.

Open Source Developers

Rust is for people who want to build the Rust programming language, community, developer tools, and libraries. We’d love to have you contribute to the Rust language.

People Who Value Speed and Stability

Rust is for people who crave speed and stability in a language. By speed, we mean both how quickly Rust code can run and the speed at which Rust lets you write programs. The Rust compiler’s checks ensure stability through feature additions and refactoring. This is in contrast to the brittle legacy code in languages without these checks, which developers are often afraid to modify. By striving for zero-cost abstractions—higher-level features that compile to lower-level code as fast as code written manually—Rust endeavors to make safe code be fast code as well.

The Rust language hopes to support many other users as well; those mentioned here are merely some of the biggest stakeholders. Overall, Rust’s greatest ambition is to eliminate the trade-offs that programmers have accepted for decades by providing safety and productivity, speed and ergonomics. Give Rust a try, and see if its choices work for you.

Who This Book Is For

This book assumes that you’ve written code in another programming language, but it doesn’t make any assumptions about which one. We’ve tried to make the material broadly accessible to those from a wide variety of programming backgrounds. We don’t spend a lot of time talking about what programming is or how to think about it. If you’re entirely new to programming, you would be better served by reading a book that specifically provides an introduction to programming.

How to Use This Book

In general, this book assumes that you’re reading it in sequence from front to back. Later chapters build on concepts in earlier chapters, and earlier chapters might not delve into details on a particular topic but will revisit the topic in a later chapter.

You’ll find two kinds of chapters in this book: concept chapters and project chapters. In concept chapters, you’ll learn about an aspect of Rust. In project chapters, we’ll build small programs together, applying what you’ve learned so far. Chapter 2, Chapter 12, and Chapter 21 are project chapters; the rest are concept chapters.

Chapter 1 explains how to install Rust, how to write a “Hello, world!” program, and how to use Cargo, Rust’s package manager and build tool. Chapter 2 is a hands-on introduction to writing a program in Rust, having you build up a number-guessing game. Here, we cover concepts at a high level, and later chapters will provide additional detail. If you want to get your hands dirty right away, Chapter 2 is the place for that. If you’re a particularly meticulous learner who prefers to learn every detail before moving on to the next, you might want to skip Chapter 2 and go straight to Chapter 3, which covers Rust features that are similar to those of other programming languages; then, you can return to Chapter 2 when you’d like to work on a project applying the details you’ve learned.

In Chapter 4, you’ll learn about Rust’s ownership system. Chapter 5

discusses structs and methods. Chapter 6 covers enums, match expressions,

and the if let and let...else control flow constructs. You’ll use structs

and enums to make custom types.

In Chapter 7, you’ll learn about Rust’s module system and about privacy rules for organizing your code and its public application programming interface (API). Chapter 8 discusses some common collection data structures that the standard library provides: vectors, strings, and hash maps. Chapter 9 explores Rust’s error-handling philosophy and techniques.

Chapter 10 digs into generics, traits, and lifetimes, which give you the

power to define code that applies to multiple types. Chapter 11 is all

about testing, which even with Rust’s safety guarantees is necessary to ensure

that your program’s logic is correct. In Chapter 12, we’ll build our own

implementation of a subset of functionality from the grep command line tool

that searches for text within files. For this, we’ll use many of the concepts

we discussed in the previous chapters.

Chapter 13 explores closures and iterators: features of Rust that come from functional programming languages. In Chapter 14, we’ll examine Cargo in more depth and talk about best practices for sharing your libraries with others. Chapter 15 discusses smart pointers that the standard library provides and the traits that enable their functionality.

In Chapter 16, we’ll walk through different models of concurrent programming and talk about how Rust helps you program in multiple threads fearlessly. In Chapter 17, we build on that by exploring Rust’s async and await syntax, along with tasks, futures, and streams, and the lightweight concurrency model they enable.

Chapter 18 looks at how Rust idioms compare to object-oriented programming principles you might be familiar with. Chapter 19 is a reference on patterns and pattern matching, which are powerful ways of expressing ideas throughout Rust programs. Chapter 20 contains a smorgasbord of advanced topics of interest, including unsafe Rust, macros, and more about lifetimes, traits, types, functions, and closures.

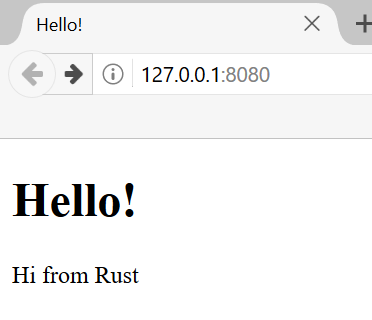

In Chapter 21, we’ll complete a project in which we’ll implement a low-level multithreaded web server!

Finally, some appendixes contain useful information about the language in a more reference-like format. Appendix A covers Rust’s keywords, Appendix B covers Rust’s operators and symbols, Appendix C covers derivable traits provided by the standard library, Appendix D covers some useful development tools, and Appendix E explains Rust editions. In Appendix F, you can find translations of the book, and in Appendix G we’ll cover how Rust is made and what nightly Rust is.

There is no wrong way to read this book: If you want to skip ahead, go for it! You might have to jump back to earlier chapters if you experience any confusion. But do whatever works for you.

An important part of the process of learning Rust is learning how to read the error messages the compiler displays: These will guide you toward working code. As such, we’ll provide many examples that don’t compile along with the error message the compiler will show you in each situation. Know that if you enter and run a random example, it may not compile! Make sure you read the surrounding text to see whether the example you’re trying to run is meant to error. In most situations, we’ll lead you to the correct version of any code that doesn’t compile. Ferris will also help you distinguish code that isn’t meant to work:

| Ferris | Meaning |

|---|---|

| This code does not compile! | |

| This code panics! | |

| This code does not produce the desired behavior. |

In most situations, we’ll lead you to the correct version of any code that doesn’t compile.

Source Code

The source files from which this book is generated can be found on GitHub.

Getting Started

Let’s start your Rust journey! There’s a lot to learn, but every journey starts somewhere. In this chapter, we’ll discuss:

- Installing Rust on Linux, macOS, and Windows

- Writing a program that prints

Hello, world! - Using

cargo, Rust’s package manager and build system

Installation

The first step is to install Rust. We’ll download Rust through rustup, a

command line tool for managing Rust versions and associated tools. You’ll need

an internet connection for the download.

Note: If you prefer not to use rustup for some reason, please see the

Other Rust Installation Methods page for more options.

The following steps install the latest stable version of the Rust compiler. Rust’s stability guarantees ensure that all the examples in the book that compile will continue to compile with newer Rust versions. The output might differ slightly between versions because Rust often improves error messages and warnings. In other words, any newer, stable version of Rust you install using these steps should work as expected with the content of this book.

Command Line Notation

In this chapter and throughout the book, we’ll show some commands used in the

terminal. Lines that you should enter in a terminal all start with $. You

don’t need to type the $ character; it’s the command line prompt shown to

indicate the start of each command. Lines that don’t start with $ typically

show the output of the previous command. Additionally, PowerShell-specific

examples will use > rather than $.

Installing rustup on Linux or macOS

If you’re using Linux or macOS, open a terminal and enter the following command:

$ curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 https://sh.rustup.rs -sSf | sh

The command downloads a script and starts the installation of the rustup

tool, which installs the latest stable version of Rust. You might be prompted

for your password. If the install is successful, the following line will appear:

Rust is installed now. Great!

You will also need a linker, which is a program that Rust uses to join its compiled outputs into one file. It is likely you already have one. If you get linker errors, you should install a C compiler, which will typically include a linker. A C compiler is also useful because some common Rust packages depend on C code and will need a C compiler.

On macOS, you can get a C compiler by running:

$ xcode-select --install

Linux users should generally install GCC or Clang, according to their

distribution’s documentation. For example, if you use Ubuntu, you can install

the build-essential package.

Installing rustup on Windows

On Windows, go to https://www.rust-lang.org/tools/install and follow the instructions for installing Rust. At some point in the installation, you’ll be prompted to install Visual Studio. This provides a linker and the native libraries needed to compile programs. If you need more help with this step, see https://rust-lang.github.io/rustup/installation/windows-msvc.html.

The rest of this book uses commands that work in both cmd.exe and PowerShell. If there are specific differences, we’ll explain which to use.

Troubleshooting

To check whether you have Rust installed correctly, open a shell and enter this line:

$ rustc --version

You should see the version number, commit hash, and commit date for the latest stable version that has been released, in the following format:

rustc x.y.z (abcabcabc yyyy-mm-dd)

If you see this information, you have installed Rust successfully! If you don’t

see this information, check that Rust is in your %PATH% system variable as

follows.

In Windows CMD, use:

> echo %PATH%

In PowerShell, use:

> echo $env:Path

In Linux and macOS, use:

$ echo $PATH

If that’s all correct and Rust still isn’t working, there are a number of places you can get help. Find out how to get in touch with other Rustaceans (a silly nickname we call ourselves) on the community page.

Updating and Uninstalling

Once Rust is installed via rustup, updating to a newly released version is

easy. From your shell, run the following update script:

$ rustup update

To uninstall Rust and rustup, run the following uninstall script from your

shell:

$ rustup self uninstall

Reading the Local Documentation

The installation of Rust also includes a local copy of the documentation so

that you can read it offline. Run rustup doc to open the local documentation

in your browser.

Any time a type or function is provided by the standard library and you’re not sure what it does or how to use it, use the application programming interface (API) documentation to find out!

Using Text Editors and IDEs

This book makes no assumptions about what tools you use to author Rust code. Just about any text editor will get the job done! However, many text editors and integrated development environments (IDEs) have built-in support for Rust. You can always find a fairly current list of many editors and IDEs on the tools page on the Rust website.

Working Offline with This Book

In several examples, we will use Rust packages beyond the standard library. To

work through those examples, you will either need to have an internet connection

or to have downloaded those dependencies ahead of time. To download the

dependencies ahead of time, you can run the following commands. (We’ll explain

what cargo is and what each of these commands does in detail later.)

$ cargo new get-dependencies

$ cd get-dependencies

$ cargo add rand@0.8.5 trpl@0.2.0

This will cache the downloads for these packages so you will not need to

download them later. Once you have run this command, you do not need to keep the

get-dependencies folder. If you have run this command, you can use the

--offline flag with all cargo commands in the rest of the book to use these

cached versions instead of attempting to use the network.

Hello, World!

Now that you’ve installed Rust, it’s time to write your first Rust program.

It’s traditional when learning a new language to write a little program that

prints the text Hello, world! to the screen, so we’ll do the same here!

Note: This book assumes basic familiarity with the command line. Rust makes

no specific demands about your editing or tooling or where your code lives, so

if you prefer to use an IDE instead of the command line, feel free to use your

favorite IDE. Many IDEs now have some degree of Rust support; check the IDE’s

documentation for details. The Rust team has been focusing on enabling great

IDE support via rust-analyzer. See Appendix D

for more details.

Project Directory Setup

You’ll start by making a directory to store your Rust code. It doesn’t matter to Rust where your code lives, but for the exercises and projects in this book, we suggest making a projects directory in your home directory and keeping all your projects there.

Open a terminal and enter the following commands to make a projects directory and a directory for the “Hello, world!” project within the projects directory.

For Linux, macOS, and PowerShell on Windows, enter this:

$ mkdir ~/projects

$ cd ~/projects

$ mkdir hello_world

$ cd hello_world

For Windows CMD, enter this:

> mkdir "%USERPROFILE%\projects"

> cd /d "%USERPROFILE%\projects"

> mkdir hello_world

> cd hello_world

Rust Program Basics

Next, make a new source file and call it main.rs. Rust files always end with the .rs extension. If you’re using more than one word in your filename, the convention is to use an underscore to separate them. For example, use hello_world.rs rather than helloworld.rs.

Now open the main.rs file you just created and enter the code in Listing 1-1.

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Hello, world!Save the file and go back to your terminal window in the ~/projects/hello_world directory. On Linux or macOS, enter the following commands to compile and run the file:

$ rustc main.rs

$ ./main

Hello, world!

On Windows, enter the command .\main instead of ./main:

> rustc main.rs

> .\main

Hello, world!

Regardless of your operating system, the string Hello, world! should print to

the terminal. If you don’t see this output, refer back to the

“Troubleshooting” part of the Installation

section for ways to get help.

If Hello, world! did print, congratulations! You’ve officially written a Rust

program. That makes you a Rust programmer—welcome!

The Anatomy of a Rust Program

Let’s review this “Hello, world!” program in detail. Here’s the first piece of the puzzle:

fn main() { }

These lines define a function named main. The main function is special: It

is always the first code that runs in every executable Rust program. Here, the

first line declares a function named main that has no parameters and returns

nothing. If there were parameters, they would go inside the parentheses (()).

The function body is wrapped in {}. Rust requires curly brackets around all

function bodies. It’s good style to place the opening curly bracket on the same

line as the function declaration, adding one space in between.

Note: If you want to stick to a standard style across Rust projects, you can

use an automatic formatter tool called rustfmt to format your code in a

particular style (more on rustfmt in

Appendix D). The Rust team has included this tool

with the standard Rust distribution, as rustc is, so it should already be

installed on your computer!

The body of the main function holds the following code:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

This line does all the work in this little program: It prints text to the screen. There are three important details to notice here.

First, println! calls a Rust macro. If it had called a function instead, it

would be entered as println (without the !). Rust macros are a way to write

code that generates code to extend Rust syntax, and we’ll discuss them in more

detail in Chapter 20. For now, you just need to

know that using a ! means that you’re calling a macro instead of a normal

function and that macros don’t always follow the same rules as functions.

Second, you see the "Hello, world!" string. We pass this string as an argument

to println!, and the string is printed to the screen.

Third, we end the line with a semicolon (;), which indicates that this

expression is over, and the next one is ready to begin. Most lines of Rust code

end with a semicolon.

Compilation and Execution

You’ve just run a newly created program, so let’s examine each step in the process.

Before running a Rust program, you must compile it using the Rust compiler by

entering the rustc command and passing it the name of your source file, like

this:

$ rustc main.rs

If you have a C or C++ background, you’ll notice that this is similar to gcc

or clang. After compiling successfully, Rust outputs a binary executable.

On Linux, macOS, and PowerShell on Windows, you can see the executable by

entering the ls command in your shell:

$ ls

main main.rs

On Linux and macOS, you’ll see two files. With PowerShell on Windows, you’ll see the same three files that you would see using CMD. With CMD on Windows, you would enter the following:

> dir /B %= the /B option says to only show the file names =%

main.exe

main.pdb

main.rs

This shows the source code file with the .rs extension, the executable file (main.exe on Windows, but main on all other platforms), and, when using Windows, a file containing debugging information with the .pdb extension. From here, you run the main or main.exe file, like this:

$ ./main # or .\main on Windows

If your main.rs is your “Hello, world!” program, this line prints Hello, world! to your terminal.

If you’re more familiar with a dynamic language, such as Ruby, Python, or JavaScript, you might not be used to compiling and running a program as separate steps. Rust is an ahead-of-time compiled language, meaning you can compile a program and give the executable to someone else, and they can run it even without having Rust installed. If you give someone a .rb, .py, or .js file, they need to have a Ruby, Python, or JavaScript implementation installed (respectively). But in those languages, you only need one command to compile and run your program. Everything is a trade-off in language design.

Just compiling with rustc is fine for simple programs, but as your project

grows, you’ll want to manage all the options and make it easy to share your

code. Next, we’ll introduce you to the Cargo tool, which will help you write

real-world Rust programs.

Hello, Cargo!

Cargo is Rust’s build system and package manager. Most Rustaceans use this tool to manage their Rust projects because Cargo handles a lot of tasks for you, such as building your code, downloading the libraries your code depends on, and building those libraries. (We call the libraries that your code needs dependencies.)

The simplest Rust programs, like the one we’ve written so far, don’t have any dependencies. If we had built the “Hello, world!” project with Cargo, it would only use the part of Cargo that handles building your code. As you write more complex Rust programs, you’ll add dependencies, and if you start a project using Cargo, adding dependencies will be much easier to do.

Because the vast majority of Rust projects use Cargo, the rest of this book assumes that you’re using Cargo too. Cargo comes installed with Rust if you used the official installers discussed in the “Installation” section. If you installed Rust through some other means, check whether Cargo is installed by entering the following in your terminal:

$ cargo --version

If you see a version number, you have it! If you see an error, such as command not found, look at the documentation for your method of installation to

determine how to install Cargo separately.

Creating a Project with Cargo

Let’s create a new project using Cargo and look at how it differs from our original “Hello, world!” project. Navigate back to your projects directory (or wherever you decided to store your code). Then, on any operating system, run the following:

$ cargo new hello_cargo

$ cd hello_cargo

The first command creates a new directory and project called hello_cargo. We’ve named our project hello_cargo, and Cargo creates its files in a directory of the same name.

Go into the hello_cargo directory and list the files. You’ll see that Cargo has generated two files and one directory for us: a Cargo.toml file and a src directory with a main.rs file inside.

It has also initialized a new Git repository along with a .gitignore file.

Git files won’t be generated if you run cargo new within an existing Git

repository; you can override this behavior by using cargo new --vcs=git.

Note: Git is a common version control system. You can change cargo new to

use a different version control system or no version control system by using

the --vcs flag. Run cargo new --help to see the available options.

Open Cargo.toml in your text editor of choice. It should look similar to the code in Listing 1-2.

[package]

name = "hello_cargo"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

cargo newThis file is in the TOML (Tom’s Obvious, Minimal Language) format, which is Cargo’s configuration format.

The first line, [package], is a section heading that indicates that the

following statements are configuring a package. As we add more information to

this file, we’ll add other sections.

The next three lines set the configuration information Cargo needs to compile

your program: the name, the version, and the edition of Rust to use. We’ll talk

about the edition key in Appendix E.

The last line, [dependencies], is the start of a section for you to list any

of your project’s dependencies. In Rust, packages of code are referred to as

crates. We won’t need any other crates for this project, but we will in the

first project in Chapter 2, so we’ll use this dependencies section then.

Now open src/main.rs and take a look:

Filename: src/main.rs

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Cargo has generated a “Hello, world!” program for you, just like the one we wrote in Listing 1-1! So far, the differences between our project and the project Cargo generated are that Cargo placed the code in the src directory, and we have a Cargo.toml configuration file in the top directory.

Cargo expects your source files to live inside the src directory. The top-level project directory is just for README files, license information, configuration files, and anything else not related to your code. Using Cargo helps you organize your projects. There’s a place for everything, and everything is in its place.

If you started a project that doesn’t use Cargo, as we did with the “Hello,

world!” project, you can convert it to a project that does use Cargo. Move the

project code into the src directory and create an appropriate Cargo.toml

file. One easy way to get that Cargo.toml file is to run cargo init, which

will create it for you automatically.

Building and Running a Cargo Project

Now let’s look at what’s different when we build and run the “Hello, world!” program with Cargo! From your hello_cargo directory, build your project by entering the following command:

$ cargo build

Compiling hello_cargo v0.1.0 (file:///projects/hello_cargo)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 2.85 secs

This command creates an executable file in target/debug/hello_cargo (or target\debug\hello_cargo.exe on Windows) rather than in your current directory. Because the default build is a debug build, Cargo puts the binary in a directory named debug. You can run the executable with this command:

$ ./target/debug/hello_cargo # or .\target\debug\hello_cargo.exe on Windows

Hello, world!

If all goes well, Hello, world! should print to the terminal. Running cargo build for the first time also causes Cargo to create a new file at the top

level: Cargo.lock. This file keeps track of the exact versions of

dependencies in your project. This project doesn’t have dependencies, so the

file is a bit sparse. You won’t ever need to change this file manually; Cargo

manages its contents for you.

We just built a project with cargo build and ran it with

./target/debug/hello_cargo, but we can also use cargo run to compile the

code and then run the resultant executable all in one command:

$ cargo run

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.0 secs

Running `target/debug/hello_cargo`

Hello, world!

Using cargo run is more convenient than having to remember to run cargo build and then use the whole path to the binary, so most developers use cargo run.

Notice that this time we didn’t see output indicating that Cargo was compiling

hello_cargo. Cargo figured out that the files hadn’t changed, so it didn’t

rebuild but just ran the binary. If you had modified your source code, Cargo

would have rebuilt the project before running it, and you would have seen this

output:

$ cargo run

Compiling hello_cargo v0.1.0 (file:///projects/hello_cargo)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.33 secs

Running `target/debug/hello_cargo`

Hello, world!

Cargo also provides a command called cargo check. This command quickly checks

your code to make sure it compiles but doesn’t produce an executable:

$ cargo check

Checking hello_cargo v0.1.0 (file:///projects/hello_cargo)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.32 secs

Why would you not want an executable? Often, cargo check is much faster than

cargo build because it skips the step of producing an executable. If you’re

continually checking your work while writing the code, using cargo check will

speed up the process of letting you know if your project is still compiling! As

such, many Rustaceans run cargo check periodically as they write their

program to make sure it compiles. Then, they run cargo build when they’re

ready to use the executable.

Let’s recap what we’ve learned so far about Cargo:

- We can create a project using

cargo new. - We can build a project using

cargo build. - We can build and run a project in one step using

cargo run. - We can build a project without producing a binary to check for errors using

cargo check. - Instead of saving the result of the build in the same directory as our code, Cargo stores it in the target/debug directory.

An additional advantage of using Cargo is that the commands are the same no matter which operating system you’re working on. So, at this point, we’ll no longer provide specific instructions for Linux and macOS versus Windows.

Building for Release

When your project is finally ready for release, you can use cargo build --release to compile it with optimizations. This command will create an

executable in target/release instead of target/debug. The optimizations

make your Rust code run faster, but turning them on lengthens the time it takes

for your program to compile. This is why there are two different profiles: one

for development, when you want to rebuild quickly and often, and another for

building the final program you’ll give to a user that won’t be rebuilt

repeatedly and that will run as fast as possible. If you’re benchmarking your

code’s running time, be sure to run cargo build --release and benchmark with

the executable in target/release.

Leveraging Cargo’s Conventions

With simple projects, Cargo doesn’t provide a lot of value over just using

rustc, but it will prove its worth as your programs become more intricate.

Once programs grow to multiple files or need a dependency, it’s much easier to

let Cargo coordinate the build.

Even though the hello_cargo project is simple, it now uses much of the real

tooling you’ll use in the rest of your Rust career. In fact, to work on any

existing projects, you can use the following commands to check out the code

using Git, change to that project’s directory, and build:

$ git clone example.org/someproject

$ cd someproject

$ cargo build

For more information about Cargo, check out its documentation.

Summary

You’re already off to a great start on your Rust journey! In this chapter, you learned how to:

- Install the latest stable version of Rust using

rustup. - Update to a newer Rust version.

- Open locally installed documentation.

- Write and run a “Hello, world!” program using

rustcdirectly. - Create and run a new project using the conventions of Cargo.

This is a great time to build a more substantial program to get used to reading and writing Rust code. So, in Chapter 2, we’ll build a guessing game program. If you would rather start by learning how common programming concepts work in Rust, see Chapter 3 and then return to Chapter 2.

Programming a Guessing Game

Let’s jump into Rust by working through a hands-on project together! This

chapter introduces you to a few common Rust concepts by showing you how to use

them in a real program. You’ll learn about let, match, methods, associated

functions, external crates, and more! In the following chapters, we’ll explore

these ideas in more detail. In this chapter, you’ll just practice the

fundamentals.

We’ll implement a classic beginner programming problem: a guessing game. Here’s how it works: The program will generate a random integer between 1 and 100. It will then prompt the player to enter a guess. After a guess is entered, the program will indicate whether the guess is too low or too high. If the guess is correct, the game will print a congratulatory message and exit.

Setting Up a New Project

To set up a new project, go to the projects directory that you created in Chapter 1 and make a new project using Cargo, like so:

$ cargo new guessing_game

$ cd guessing_game

The first command, cargo new, takes the name of the project (guessing_game)

as the first argument. The second command changes to the new project’s

directory.

Look at the generated Cargo.toml file:

Filename: Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "guessing_game"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

As you saw in Chapter 1, cargo new generates a “Hello, world!” program for

you. Check out the src/main.rs file:

Filename: src/main.rs

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Now let’s compile this “Hello, world!” program and run it in the same step

using the cargo run command:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.08s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Hello, world!

The run command comes in handy when you need to rapidly iterate on a project,

as we’ll do in this game, quickly testing each iteration before moving on to

the next one.

Reopen the src/main.rs file. You’ll be writing all the code in this file.

Processing a Guess

The first part of the guessing game program will ask for user input, process that input, and check that the input is in the expected form. To start, we’ll allow the player to input a guess. Enter the code in Listing 2-1 into src/main.rs.

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}This code contains a lot of information, so let’s go over it line by line. To

obtain user input and then print the result as output, we need to bring the

io input/output library into scope. The io library comes from the standard

library, known as std:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}By default, Rust has a set of items defined in the standard library that it brings into the scope of every program. This set is called the prelude, and you can see everything in it in the standard library documentation.

If a type you want to use isn’t in the prelude, you have to bring that type

into scope explicitly with a use statement. Using the std::io library

provides you with a number of useful features, including the ability to accept

user input.

As you saw in Chapter 1, the main function is the entry point into the

program:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}The fn syntax declares a new function; the parentheses, (), indicate there

are no parameters; and the curly bracket, {, starts the body of the function.

As you also learned in Chapter 1, println! is a macro that prints a string to

the screen:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}This code is printing a prompt stating what the game is and requesting input from the user.

Storing Values with Variables

Next, we’ll create a variable to store the user input, like this:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}Now the program is getting interesting! There’s a lot going on in this little

line. We use the let statement to create the variable. Here’s another example:

let apples = 5;This line creates a new variable named apples and binds it to the value 5.

In Rust, variables are immutable by default, meaning once we give the variable

a value, the value won’t change. We’ll be discussing this concept in detail in

the “Variables and Mutability”

section in Chapter 3. To make a variable mutable, we add mut before the

variable name:

let apples = 5; // immutable

let mut bananas = 5; // mutableNote: The // syntax starts a comment that continues until the end of the

line. Rust ignores everything in comments. We’ll discuss comments in more

detail in Chapter 3.

Returning to the guessing game program, you now know that let mut guess will

introduce a mutable variable named guess. The equal sign (=) tells Rust we

want to bind something to the variable now. On the right of the equal sign is

the value that guess is bound to, which is the result of calling

String::new, a function that returns a new instance of a String.

String is a string type provided by the standard

library that is a growable, UTF-8 encoded bit of text.

The :: syntax in the ::new line indicates that new is an associated

function of the String type. An associated function is a function that’s

implemented on a type, in this case String. This new function creates a

new, empty string. You’ll find a new function on many types because it’s a

common name for a function that makes a new value of some kind.

In full, the let mut guess = String::new(); line has created a mutable

variable that is currently bound to a new, empty instance of a String. Whew!

Receiving User Input

Recall that we included the input/output functionality from the standard

library with use std::io; on the first line of the program. Now we’ll call

the stdin function from the io module, which will allow us to handle user

input:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}If we hadn’t imported the io module with use std::io; at the beginning of

the program, we could still use the function by writing this function call as

std::io::stdin. The stdin function returns an instance of

std::io::Stdin, which is a type that represents a

handle to the standard input for your terminal.

Next, the line .read_line(&mut guess) calls the read_line method on the standard input handle to get input from the user.

We’re also passing &mut guess as the argument to read_line to tell it what

string to store the user input in. The full job of read_line is to take

whatever the user types into standard input and append that into a string

(without overwriting its contents), so we therefore pass that string as an

argument. The string argument needs to be mutable so that the method can change

the string’s content.

The & indicates that this argument is a reference, which gives you a way to

let multiple parts of your code access one piece of data without needing to

copy that data into memory multiple times. References are a complex feature,

and one of Rust’s major advantages is how safe and easy it is to use

references. You don’t need to know a lot of those details to finish this

program. For now, all you need to know is that, like variables, references are

immutable by default. Hence, you need to write &mut guess rather than

&guess to make it mutable. (Chapter 4 will explain references more

thoroughly.)

Handling Potential Failure with Result

We’re still working on this line of code. We’re now discussing a third line of text, but note that it’s still part of a single logical line of code. The next part is this method:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}We could have written this code as:

io::stdin().read_line(&mut guess).expect("Failed to read line");However, one long line is difficult to read, so it’s best to divide it. It’s

often wise to introduce a newline and other whitespace to help break up long

lines when you call a method with the .method_name() syntax. Now let’s

discuss what this line does.

As mentioned earlier, read_line puts whatever the user enters into the string

we pass to it, but it also returns a Result value. Result is an enumeration, often called an enum,

which is a type that can be in one of multiple possible states. We call each

possible state a variant.

Chapter 6 will cover enums in more detail. The purpose

of these Result types is to encode error-handling information.

Result’s variants are Ok and Err. The Ok variant indicates the

operation was successful, and it contains the successfully generated value.

The Err variant means the operation failed, and it contains information

about how or why the operation failed.

Values of the Result type, like values of any type, have methods defined on

them. An instance of Result has an expect method

that you can call. If this instance of Result is an Err value, expect

will cause the program to crash and display the message that you passed as an

argument to expect. If the read_line method returns an Err, it would

likely be the result of an error coming from the underlying operating system.

If this instance of Result is an Ok value, expect will take the return

value that Ok is holding and return just that value to you so that you can

use it. In this case, that value is the number of bytes in the user’s input.

If you don’t call expect, the program will compile, but you’ll get a warning:

$ cargo build

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

warning: unused `Result` that must be used

--> src/main.rs:10:5

|

10 | io::stdin().read_line(&mut guess);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

|

= note: this `Result` may be an `Err` variant, which should be handled

= note: `#[warn(unused_must_use)]` on by default

help: use `let _ = ...` to ignore the resulting value

|

10 | let _ = io::stdin().read_line(&mut guess);

| +++++++

warning: `guessing_game` (bin "guessing_game") generated 1 warning

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.59s

Rust warns that you haven’t used the Result value returned from read_line,

indicating that the program hasn’t handled a possible error.

The right way to suppress the warning is to actually write error-handling code,

but in our case we just want to crash this program when a problem occurs, so we

can use expect. You’ll learn about recovering from errors in Chapter

9.

Printing Values with println! Placeholders

Aside from the closing curly bracket, there’s only one more line to discuss in the code so far:

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}This line prints the string that now contains the user’s input. The {} set of

curly brackets is a placeholder: Think of {} as little crab pincers that hold

a value in place. When printing the value of a variable, the variable name can

go inside the curly brackets. When printing the result of evaluating an

expression, place empty curly brackets in the format string, then follow the

format string with a comma-separated list of expressions to print in each empty

curly bracket placeholder in the same order. Printing a variable and the result

of an expression in one call to println! would look like this:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let x = 5; let y = 10; println!("x = {x} and y + 2 = {}", y + 2); }

This code would print x = 5 and y + 2 = 12.

Testing the First Part

Let’s test the first part of the guessing game. Run it using cargo run:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 6.44s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Guess the number!

Please input your guess.

6

You guessed: 6

At this point, the first part of the game is done: We’re getting input from the keyboard and then printing it.

Generating a Secret Number

Next, we need to generate a secret number that the user will try to guess. The

secret number should be different every time so that the game is fun to play

more than once. We’ll use a random number between 1 and 100 so that the game

isn’t too difficult. Rust doesn’t yet include random number functionality in

its standard library. However, the Rust team does provide a rand

crate with said functionality.

Increasing Functionality with a Crate

Remember that a crate is a collection of Rust source code files. The project

we’ve been building is a binary crate, which is an executable. The rand crate

is a library crate, which contains code that is intended to be used in other

programs and can’t be executed on its own.

Cargo’s coordination of external crates is where Cargo really shines. Before we

can write code that uses rand, we need to modify the Cargo.toml file to

include the rand crate as a dependency. Open that file now and add the

following line to the bottom, beneath the [dependencies] section header that

Cargo created for you. Be sure to specify rand exactly as we have here, with

this version number, or the code examples in this tutorial may not work:

Filename: Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.5"

In the Cargo.toml file, everything that follows a header is part of that

section that continues until another section starts. In [dependencies], you

tell Cargo which external crates your project depends on and which versions of

those crates you require. In this case, we specify the rand crate with the

semantic version specifier 0.8.5. Cargo understands Semantic

Versioning (sometimes called SemVer), which is a

standard for writing version numbers. The specifier 0.8.5 is actually

shorthand for ^0.8.5, which means any version that is at least 0.8.5 but

below 0.9.0.

Cargo considers these versions to have public APIs compatible with version 0.8.5, and this specification ensures that you’ll get the latest patch release that will still compile with the code in this chapter. Any version 0.9.0 or greater is not guaranteed to have the same API as what the following examples use.

Now, without changing any of the code, let’s build the project, as shown in Listing 2-2.

$ cargo build

Updating crates.io index

Locking 15 packages to latest Rust 1.85.0 compatible versions

Adding rand v0.8.5 (available: v0.9.0)

Compiling proc-macro2 v1.0.93

Compiling unicode-ident v1.0.17

Compiling libc v0.2.170

Compiling cfg-if v1.0.0

Compiling byteorder v1.5.0

Compiling getrandom v0.2.15

Compiling rand_core v0.6.4

Compiling quote v1.0.38

Compiling syn v2.0.98

Compiling zerocopy-derive v0.7.35

Compiling zerocopy v0.7.35

Compiling ppv-lite86 v0.2.20

Compiling rand_chacha v0.3.1

Compiling rand v0.8.5

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 2.48s

cargo build after adding the rand crate as a dependencyYou may see different version numbers (but they will all be compatible with the code, thanks to SemVer!) and different lines (depending on the operating system), and the lines may be in a different order.

When we include an external dependency, Cargo fetches the latest versions of everything that dependency needs from the registry, which is a copy of data from Crates.io. Crates.io is where people in the Rust ecosystem post their open source Rust projects for others to use.

After updating the registry, Cargo checks the [dependencies] section and

downloads any crates listed that aren’t already downloaded. In this case,

although we only listed rand as a dependency, Cargo also grabbed other crates

that rand depends on to work. After downloading the crates, Rust compiles

them and then compiles the project with the dependencies available.

If you immediately run cargo build again without making any changes, you

won’t get any output aside from the Finished line. Cargo knows it has already

downloaded and compiled the dependencies, and you haven’t changed anything

about them in your Cargo.toml file. Cargo also knows that you haven’t changed

anything about your code, so it doesn’t recompile that either. With nothing to

do, it simply exits.

If you open the src/main.rs file, make a trivial change, and then save it and build again, you’ll only see two lines of output:

$ cargo build

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.13s

These lines show that Cargo only updates the build with your tiny change to the src/main.rs file. Your dependencies haven’t changed, so Cargo knows it can reuse what it has already downloaded and compiled for those.

Ensuring Reproducible Builds

Cargo has a mechanism that ensures that you can rebuild the same artifact every

time you or anyone else builds your code: Cargo will use only the versions of

the dependencies you specified until you indicate otherwise. For example, say

that next week version 0.8.6 of the rand crate comes out, and that version

contains an important bug fix, but it also contains a regression that will

break your code. To handle this, Rust creates the Cargo.lock file the first

time you run cargo build, so we now have this in the guessing_game

directory.

When you build a project for the first time, Cargo figures out all the versions of the dependencies that fit the criteria and then writes them to the Cargo.lock file. When you build your project in the future, Cargo will see that the Cargo.lock file exists and will use the versions specified there rather than doing all the work of figuring out versions again. This lets you have a reproducible build automatically. In other words, your project will remain at 0.8.5 until you explicitly upgrade, thanks to the Cargo.lock file. Because the Cargo.lock file is important for reproducible builds, it’s often checked into source control with the rest of the code in your project.

Updating a Crate to Get a New Version

When you do want to update a crate, Cargo provides the command update,

which will ignore the Cargo.lock file and figure out all the latest versions

that fit your specifications in Cargo.toml. Cargo will then write those

versions to the Cargo.lock file. Otherwise, by default, Cargo will only look

for versions greater than 0.8.5 and less than 0.9.0. If the rand crate has

released the two new versions 0.8.6 and 0.999.0, you would see the following if

you ran cargo update:

$ cargo update

Updating crates.io index

Locking 1 package to latest Rust 1.85.0 compatible version

Updating rand v0.8.5 -> v0.8.6 (available: v0.999.0)

Cargo ignores the 0.999.0 release. At this point, you would also notice a

change in your Cargo.lock file noting that the version of the rand crate

you are now using is 0.8.6. To use rand version 0.999.0 or any version in the

0.999.x series, you’d have to update the Cargo.toml file to look like this

instead (don’t actually make this change because the following examples assume

you’re using rand 0.8):

[dependencies]

rand = "0.999.0"

The next time you run cargo build, Cargo will update the registry of crates

available and reevaluate your rand requirements according to the new version

you have specified.

There’s a lot more to say about Cargo and its ecosystem, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 14, but for now, that’s all you need to know. Cargo makes it very easy to reuse libraries, so Rustaceans are able to write smaller projects that are assembled from a number of packages.

Generating a Random Number

Let’s start using rand to generate a number to guess. The next step is to

update src/main.rs, as shown in Listing 2-3.

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

}First, we add the line use rand::Rng;. The Rng trait defines methods that

random number generators implement, and this trait must be in scope for us to

use those methods. Chapter 10 will cover traits in detail.

Next, we’re adding two lines in the middle. In the first line, we call the

rand::thread_rng function that gives us the particular random number

generator we’re going to use: one that is local to the current thread of

execution and is seeded by the operating system. Then, we call the gen_range

method on the random number generator. This method is defined by the Rng

trait that we brought into scope with the use rand::Rng; statement. The

gen_range method takes a range expression as an argument and generates a

random number in the range. The kind of range expression we’re using here takes

the form start..=end and is inclusive on the lower and upper bounds, so we

need to specify 1..=100 to request a number between 1 and 100.

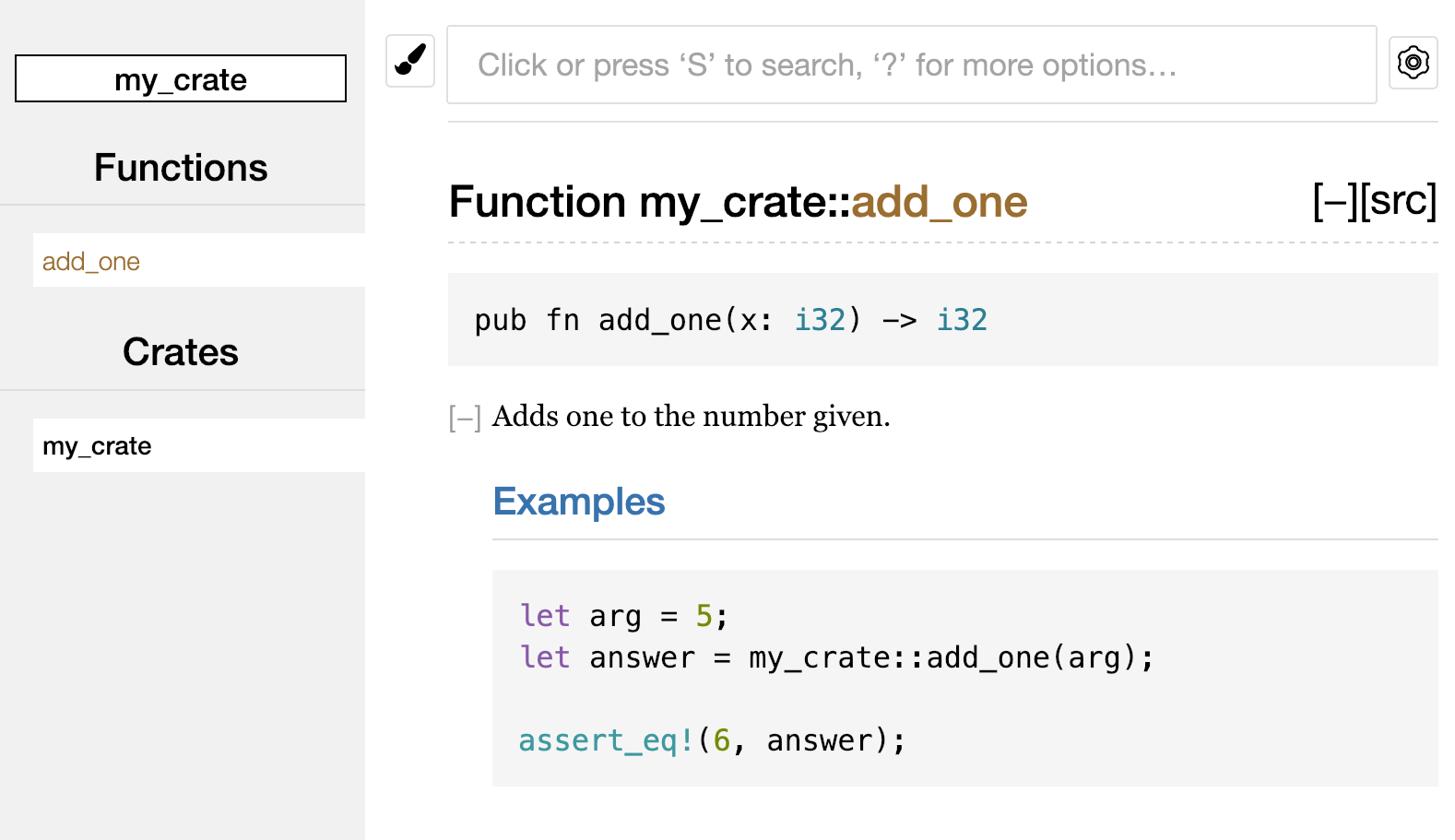

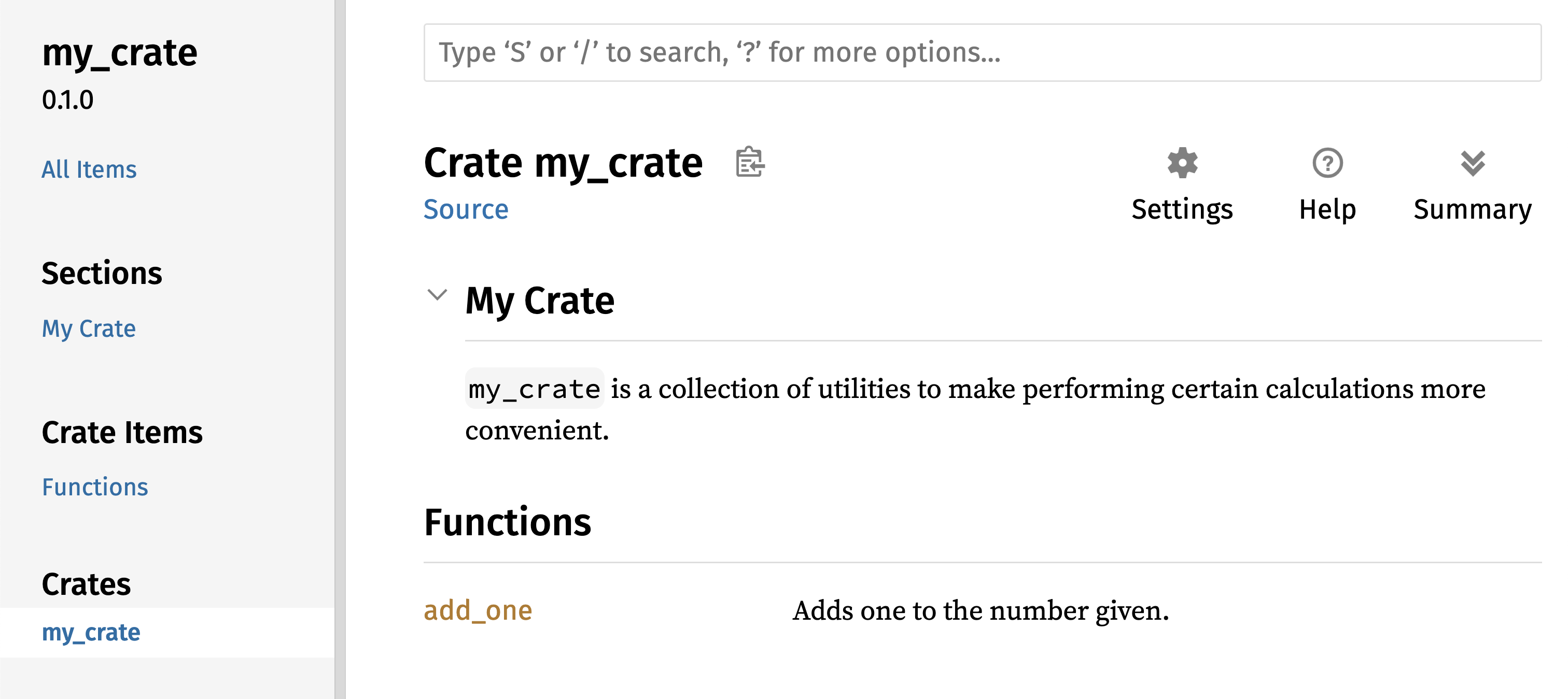

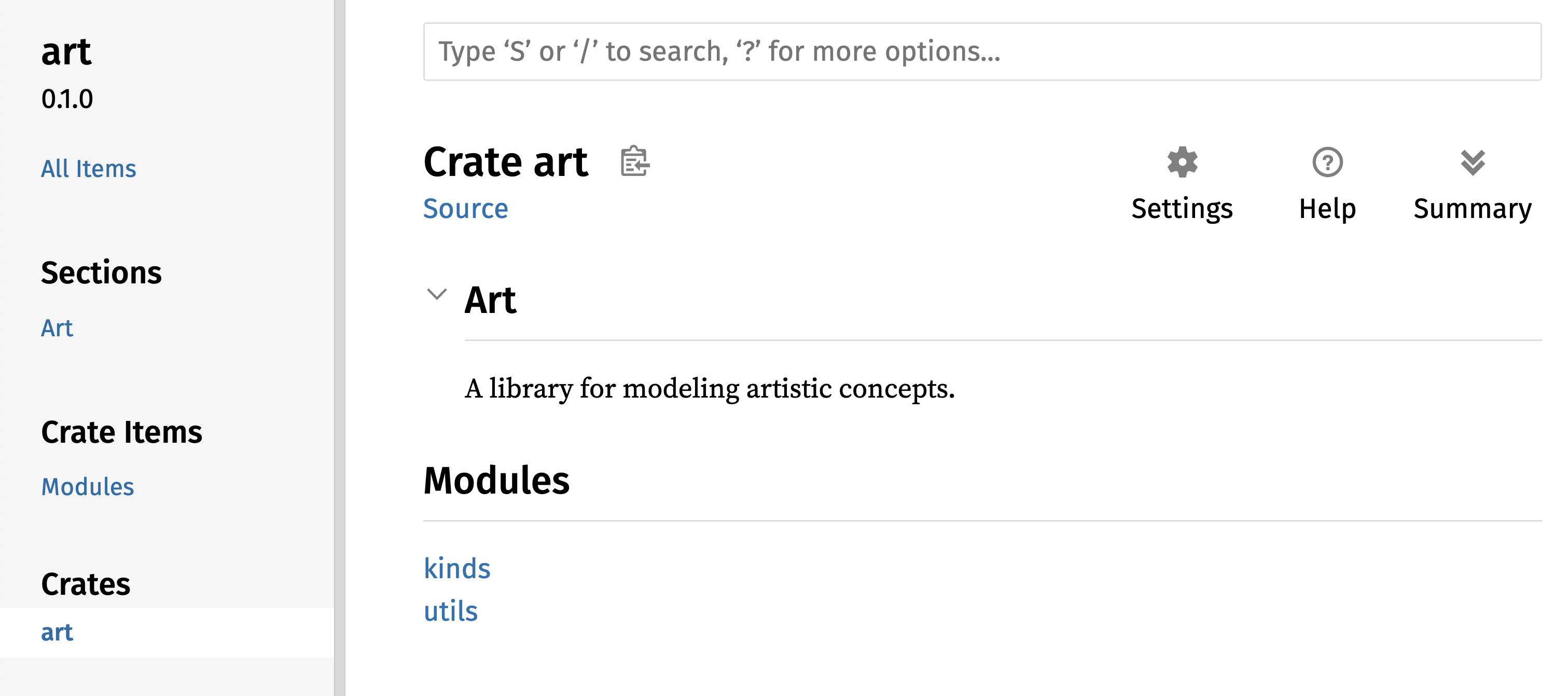

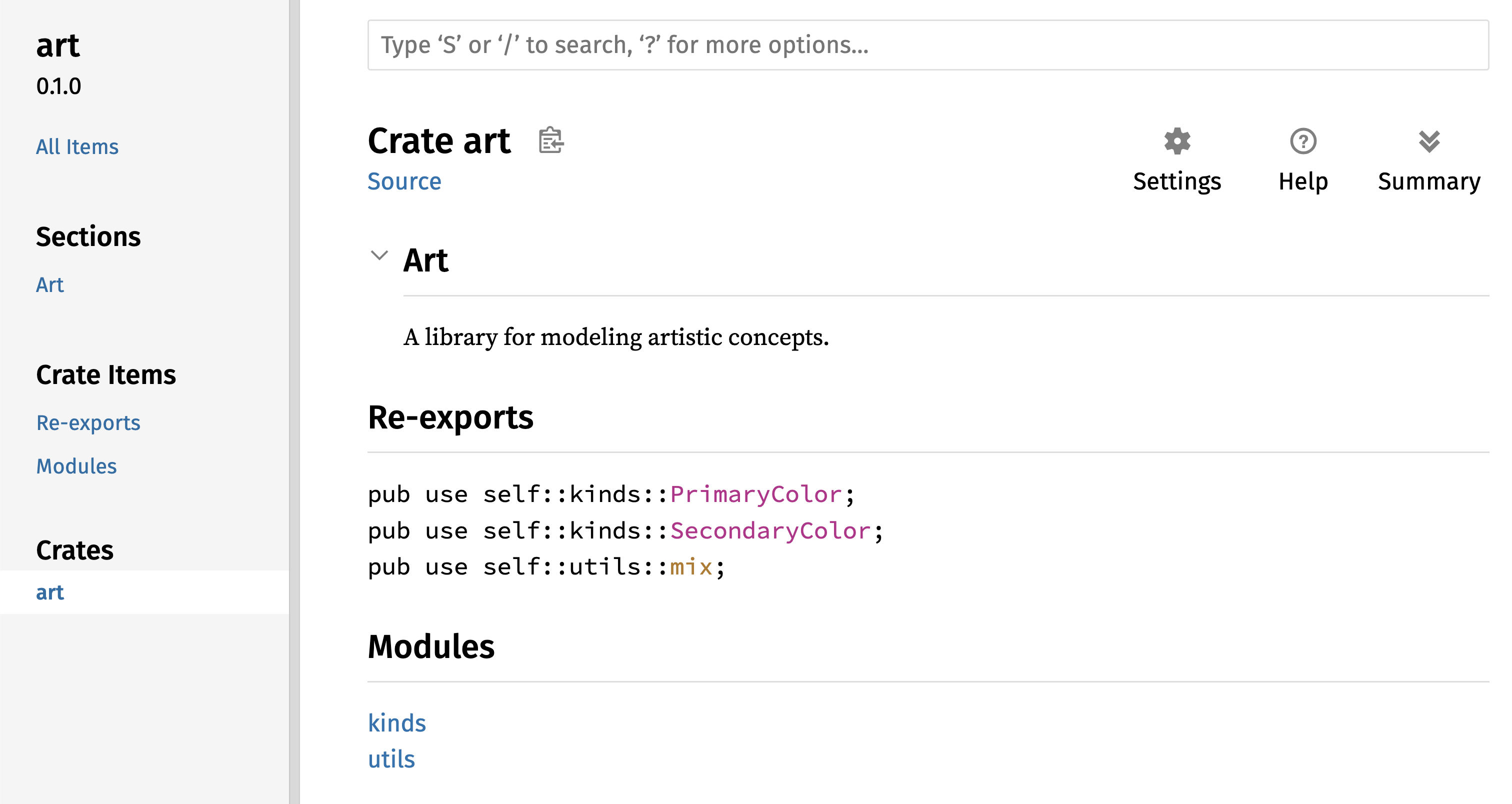

Note: You won’t just know which traits to use and which methods and functions

to call from a crate, so each crate has documentation with instructions for

using it. Another neat feature of Cargo is that running the cargo doc --open command will build documentation provided by all your dependencies

locally and open it in your browser. If you’re interested in other

functionality in the rand crate, for example, run cargo doc --open and

click rand in the sidebar on the left.

The second new line prints the secret number. This is useful while we’re developing the program to be able to test it, but we’ll delete it from the final version. It’s not much of a game if the program prints the answer as soon as it starts!

Try running the program a few times:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Guess the number!

The secret number is: 7

Please input your guess.

4

You guessed: 4

$ cargo run

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Guess the number!

The secret number is: 83

Please input your guess.

5

You guessed: 5

You should get different random numbers, and they should all be numbers between 1 and 100. Great job!

Comparing the Guess to the Secret Number

Now that we have user input and a random number, we can compare them. That step is shown in Listing 2-4. Note that this code won’t compile just yet, as we will explain.

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

// --snip--

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => println!("You win!"),

}

}First, we add another use statement, bringing a type called

std::cmp::Ordering into scope from the standard library. The Ordering type

is another enum and has the variants Less, Greater, and Equal. These are

the three outcomes that are possible when you compare two values.

Then, we add five new lines at the bottom that use the Ordering type. The

cmp method compares two values and can be called on anything that can be

compared. It takes a reference to whatever you want to compare with: Here, it’s

comparing guess to secret_number. Then, it returns a variant of the

Ordering enum we brought into scope with the use statement. We use a

match expression to decide what to do next based on

which variant of Ordering was returned from the call to cmp with the values

in guess and secret_number.

A match expression is made up of arms. An arm consists of a pattern to

match against, and the code that should be run if the value given to match

fits that arm’s pattern. Rust takes the value given to match and looks

through each arm’s pattern in turn. Patterns and the match construct are

powerful Rust features: They let you express a variety of situations your code

might encounter, and they make sure you handle them all. These features will be

covered in detail in Chapter 6 and Chapter 19, respectively.

Let’s walk through an example with the match expression we use here. Say that

the user has guessed 50 and the randomly generated secret number this time is

38.

When the code compares 50 to 38, the cmp method will return

Ordering::Greater because 50 is greater than 38. The match expression gets

the Ordering::Greater value and starts checking each arm’s pattern. It looks

at the first arm’s pattern, Ordering::Less, and sees that the value

Ordering::Greater does not match Ordering::Less, so it ignores the code in

that arm and moves to the next arm. The next arm’s pattern is

Ordering::Greater, which does match Ordering::Greater! The associated

code in that arm will execute and print Too big! to the screen. The match

expression ends after the first successful match, so it won’t look at the last

arm in this scenario.

However, the code in Listing 2-4 won’t compile yet. Let’s try it:

$ cargo build

Compiling libc v0.2.86

Compiling getrandom v0.2.2

Compiling cfg-if v1.0.0

Compiling ppv-lite86 v0.2.10

Compiling rand_core v0.6.2

Compiling rand_chacha v0.3.0

Compiling rand v0.8.5

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

error[E0308]: mismatched types

--> src/main.rs:23:21

|

23 | match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

| --- ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected `&String`, found `&{integer}`

| |

| arguments to this method are incorrect

|

= note: expected reference `&String`

found reference `&{integer}`

note: method defined here

--> /rustc/1159e78c4747b02ef996e55082b704c09b970588/library/core/src/cmp.rs:979:8

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0308`.

error: could not compile `guessing_game` (bin "guessing_game") due to 1 previous error

The core of the error states that there are mismatched types. Rust has a

strong, static type system. However, it also has type inference. When we wrote

let mut guess = String::new(), Rust was able to infer that guess should be

a String and didn’t make us write the type. The secret_number, on the other

hand, is a number type. A few of Rust’s number types can have a value between 1

and 100: i32, a 32-bit number; u32, an unsigned 32-bit number; i64, a

64-bit number; as well as others. Unless otherwise specified, Rust defaults to

an i32, which is the type of secret_number unless you add type information

elsewhere that would cause Rust to infer a different numerical type. The reason

for the error is that Rust cannot compare a string and a number type.

Ultimately, we want to convert the String the program reads as input into a

number type so that we can compare it numerically to the secret number. We do

so by adding this line to the main function body:

Filename: src/main.rs

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

println!("Please input your guess.");

// --snip--

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

let guess: u32 = guess.trim().parse().expect("Please type a number!");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => println!("You win!"),

}

}The line is:

let guess: u32 = guess.trim().parse().expect("Please type a number!");We create a variable named guess. But wait, doesn’t the program already have

a variable named guess? It does, but helpfully Rust allows us to shadow the

previous value of guess with a new one. Shadowing lets us reuse the guess

variable name rather than forcing us to create two unique variables, such as

guess_str and guess, for example. We’ll cover this in more detail in

Chapter 3, but for now, know that this feature is

often used when you want to convert a value from one type to another type.

We bind this new variable to the expression guess.trim().parse(). The guess

in the expression refers to the original guess variable that contained the

input as a string. The trim method on a String instance will eliminate any

whitespace at the beginning and end, which we must do before we can convert the

string to a u32, which can only contain numerical data. The user must press

enter to satisfy read_line and input their guess, which adds a

newline character to the string. For example, if the user types 5 and

presses enter, guess looks like this: 5\n. The \n represents

“newline.” (On Windows, pressing enter results in a carriage return

and a newline, \r\n.) The trim method eliminates \n or \r\n, resulting

in just 5.

The parse method on strings converts a string to

another type. Here, we use it to convert from a string to a number. We need to

tell Rust the exact number type we want by using let guess: u32. The colon

(:) after guess tells Rust we’ll annotate the variable’s type. Rust has a

few built-in number types; the u32 seen here is an unsigned, 32-bit integer.

It’s a good default choice for a small positive number. You’ll learn about

other number types in Chapter 3.

Additionally, the u32 annotation in this example program and the comparison

with secret_number means Rust will infer that secret_number should be a

u32 as well. So, now the comparison will be between two values of the same

type!

The parse method will only work on characters that can logically be converted

into numbers and so can easily cause errors. If, for example, the string

contained A👍%, there would be no way to convert that to a number. Because it

might fail, the parse method returns a Result type, much as the read_line

method does (discussed earlier in “Handling Potential Failure with

Result”). We’ll treat

this Result the same way by using the expect method again. If parse

returns an Err Result variant because it couldn’t create a number from the

string, the expect call will crash the game and print the message we give it.

If parse can successfully convert the string to a number, it will return the

Ok variant of Result, and expect will return the number that we want from

the Ok value.

Let’s run the program now:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.26s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Guess the number!

The secret number is: 58

Please input your guess.

76

You guessed: 76

Too big!

Nice! Even though spaces were added before the guess, the program still figured out that the user guessed 76. Run the program a few times to verify the different behavior with different kinds of input: Guess the number correctly, guess a number that is too high, and guess a number that is too low.

We have most of the game working now, but the user can make only one guess. Let’s change that by adding a loop!

Allowing Multiple Guesses with Looping

The loop keyword creates an infinite loop. We’ll add a loop to give users

more chances at guessing the number:

Filename: src/main.rs

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

// --snip--

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

loop {

println!("Please input your guess.");

// --snip--

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

let guess: u32 = guess.trim().parse().expect("Please type a number!");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => println!("You win!"),

}

}

}As you can see, we’ve moved everything from the guess input prompt onward into a loop. Be sure to indent the lines inside the loop another four spaces each and run the program again. The program will now ask for another guess forever, which actually introduces a new problem. It doesn’t seem like the user can quit!

The user could always interrupt the program by using the keyboard shortcut

ctrl-C. But there’s another way to escape this insatiable

monster, as mentioned in the parse discussion in “Comparing the Guess to the

Secret Number”: If

the user enters a non-number answer, the program will crash. We can take

advantage of that to allow the user to quit, as shown here:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.23s

Running `target/debug/guessing_game`

Guess the number!

The secret number is: 59

Please input your guess.

45

You guessed: 45

Too small!

Please input your guess.

60

You guessed: 60

Too big!

Please input your guess.

59

You guessed: 59

You win!

Please input your guess.

quit

thread 'main' panicked at src/main.rs:28:47:

Please type a number!: ParseIntError { kind: InvalidDigit }

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

Typing quit will quit the game, but as you’ll notice, so will entering any

other non-number input. This is suboptimal, to say the least; we want the game

to also stop when the correct number is guessed.

Quitting After a Correct Guess

Let’s program the game to quit when the user wins by adding a break statement:

Filename: src/main.rs

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

loop {

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

let guess: u32 = guess.trim().parse().expect("Please type a number!");

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

// --snip--

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => {

println!("You win!");

break;

}

}

}

}Adding the break line after You win! makes the program exit the loop when

the user guesses the secret number correctly. Exiting the loop also means

exiting the program, because the loop is the last part of main.

Handling Invalid Input

To further refine the game’s behavior, rather than crashing the program when

the user inputs a non-number, let’s make the game ignore a non-number so that

the user can continue guessing. We can do that by altering the line where

guess is converted from a String to a u32, as shown in Listing 2-5.

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::io;

use rand::Rng;

fn main() {

println!("Guess the number!");

let secret_number = rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..=100);

println!("The secret number is: {secret_number}");

loop {

println!("Please input your guess.");

let mut guess = String::new();

// --snip--

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut guess)

.expect("Failed to read line");

let guess: u32 = match guess.trim().parse() {

Ok(num) => num,

Err(_) => continue,

};

println!("You guessed: {guess}");

// --snip--

match guess.cmp(&secret_number) {

Ordering::Less => println!("Too small!"),

Ordering::Greater => println!("Too big!"),

Ordering::Equal => {

println!("You win!");

break;

}

}

}

}We switch from an expect call to a match expression to move from crashing

on an error to handling the error. Remember that parse returns a Result

type and Result is an enum that has the variants Ok and Err. We’re using

a match expression here, as we did with the Ordering result of the cmp

method.

If parse is able to successfully turn the string into a number, it will

return an Ok value that contains the resultant number. That Ok value will

match the first arm’s pattern, and the match expression will just return the

num value that parse produced and put inside the Ok value. That number

will end up right where we want it in the new guess variable we’re creating.

If parse is not able to turn the string into a number, it will return an

Err value that contains more information about the error. The Err value

does not match the Ok(num) pattern in the first match arm, but it does

match the Err(_) pattern in the second arm. The underscore, _, is a

catch-all value; in this example, we’re saying we want to match all Err

values, no matter what information they have inside them. So, the program will

execute the second arm’s code, continue, which tells the program to go to the

next iteration of the loop and ask for another guess. So, effectively, the

program ignores all errors that parse might encounter!

Now everything in the program should work as expected. Let’s try it:

$ cargo run

Compiling guessing_game v0.1.0 (file:///projects/guessing_game)